Telehealth is a cost-effective alternative to health care that is provided in-person, especially for rural and underserved areas.

School-based health centers (SBHCs) use telehealth to extend their services during breaks or when students are not in school. It also allows SBHC providers to work from alternative locations as needed, and to reach students who might not be in school.

Some SBHCs use telehealth to extend the traditional boundaries of health care, for example offering yoga classes and helping lead virtual college tours.

For more information on the different modalities of telehealth, how they can apply to school-based health, and recommendations, download our overview on Telehealth in Schools & School-Based Health Centers.

Young people are open to—and already using—telehealth to meet their health needs. Schools can meet teens where they are at with the provision of telehealth services.

Telehealth has the potential to increase access to primary, specialty, and mental health care for students, particularly marginalized youth that might otherwise go without access to care due to various socioeconomic factors.

Transportation barriers are reduced for youth, parents, and guardians. Older adolescents can use telehealth to access sensitive and confidential care independently. Students and families whose primary language is not English may also be able to access more culturally and linguistically appropriate care through telehealth options.

Telehealth can also provide access to types of providers and specialists that may not be available in the immediate community.

Studies & Provider Organizations Support Telehealth in Schools

A recent study analyzing one of the largest school-based telehealth programs in the nation, based in Texas, found that such programs have the potential to reach a large pediatric population that need health care due to lapses in services because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Asthma and other respiratory disease was the primary diagnosis, demonstrating that telehealth is a good option for management of chronic conditions.

The American Academy of Pediatrics has endorsed the use of school-based telemedicine for chronic childhood disease and for those that live in rural and underserved areas.

The National Association of School Nurses also supports the use of telehealth technology to augment school health services, but not replace in-person health provided by the school nurse. Other studies have demonstrated that students with access to care through telehealth at school show improved health and education outcomes.

A 2021 report commissioned by Common Sense, Hopelab and the California Health Care Foundation on how young people use digital media to manage their mental health found that social media and online tools were a lifeline that many young people needed to get through the pandemic. Nearly half (47%) of those surveyed reported that they had connected with healthcare providers online using digital tools, including more than one in four (27%) engaging in a video appointment with a provider. The report also revealed that 65% of adolescents ages 14-17 used health-related mobile apps and 85% searched for health information online.

Equipment

- equipment to facilitate the service (computer, camera, internet connection, telehealth platform, etc.)*

- other equipment/supplies ( e.g., thermometer, otoscope) that the student or presenter can use to present relevant data to the provider*

- a confidential space where the student can be connected to a remote health care provider

Personnel

- a health care provider available through this connection to provide the services, including the ability to make referrals or schedule follow-up care if necessary, following all appropriate laws and regulations

- a coordinator for program management, billing, and scheduling, if possible

- a telehealth “presenter” who is physically available with the student and can, at minimum, link the student to the provider through the platform being utilized, or in other cases and with younger students remain throughout the visit and be involved in communicating symptoms, taking measurements, and directing future care. This can be a medical assistant, school nurse, clerk or in some cases a family member.

Systems

- a system for communicating with parents and families as appropriate

- a system for scheduling appointments, even if this is focused on walk-in or drop-in visits

- a policy for addressing consent, authorization, and information sharing

- information technology support, including a privacy and security system in place

*As needed. Some services, such as mental health, may not require some of these components if audio-only telehealth is utilized.

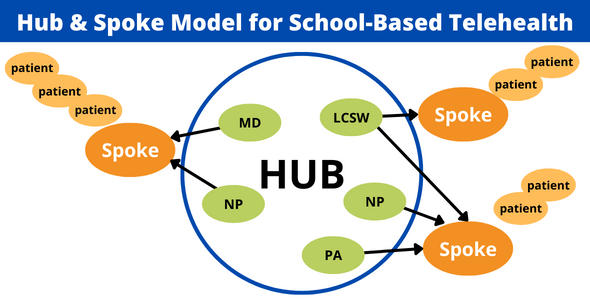

Hub and Spoke Model

A school site, SBHC, or community-based site serves as a central location, or “hub,” where clinical providers are located. Patients and presenting staff or providers, or “spokes,” are located at other locations within the collaborating system or district to support students at those sites as they are connected, via telehealth, to the providers in the “hub.” SBHCs can function as both “hubs” and “spokes” as described in the examples below.

Example 1: In Hawaii, one pediatrician located at an SBHC serves students at three other schools by having a well-trained medical assistant at the outlying school present student patients to her so that she can conduct a thorough physical exam by telehealth. This allows the physician to order vaccines and lab tests at that visit and the medical assistant to complete them. In this case, telehealth increases access for those schools and also increases the physician’s efficiency by widening the number of students she can reach and generating additional reimbursement for her SBHC, which operates as the hub.

Example 2: In West Virginia, a telemental health program was able to increase access to psychiatric services for SBHC patients who did not have access, reducing the wait time for their initial appointments. In this scenario, they set up a receiving station and equip it with appropriate technology such as a camera, computer, and monitor. Another agency then provides mental health care remotely to students who are in the SBHC location and in partnership with the staff and providers there. This example illustrates an SBHC acting as a telehealth spoke to provide specialty care beyond the scope of the SBHC services.

Example 3: Denver Public Schools is piloting a full spoke model at a high school campus that includes well-child visits and some reproductive health. It is exploring whether this model increases student access to quality health care services; early results are promising and the district is also considering a full service SBHC.This example illustrates employing a school nurse or a health technician that supports the spoke end of an enhancement model.

SBHCs can also use telehealth to extend their services during breaks or when students are not in school.

Many SBHCs provided telehealth services to students who were not in school during the COVID-19 public health emergency. A community health center in Oakland that operates eight SBHCs developed a phone triage line for youth in Oakland during the COVID pandemic when schools and SBHCs were closed and conducted hundreds of video, phone and text-based care for student patients.

Many SBHCs have transitioned to a “hybrid” model of care with some visits delivered in person and others provided via the now-established telehealth platform.

This broadens options for students and allows them choice in managing their own health. It also allows SBHC providers to work from alternative locations as needed, and to reach students who might not be in school.

Some SBHCs use telehealth to extend the traditional boundaries of health care, for example offering yoga classes and helping lead virtual college tours.

Schools without SBHCs

Schools and school districts that do not have the benefit of SBHCs and want to offer telehealth services to students can select among established telehealth providers, partner with community-based health care providers, or create their own program.

There are a number of existing agencies that provide telehealth primary care services or other telehealth services.

Hazel Health specifically focuses on providing this care in school settings. One school district in Southern California contracts with Hazel Health to deliver physical health services via telehealth for students as part of its solution to address student health and wellness.

Hazel Health provided the district with equipment such as a locked medication cart and iPad rolling cart and a series of trainings for health aides and school nurses to establish a protocol and workflow. They targeted students who experienced chronic absenteeism and students who needed additional care or coverage.

The cost to the district is based on the total number of enrolled students and the district used its Local Control and Accountability Plan (LCAP) and Learning Communities for Student Success (LCSSP) grant funding to support its subscription. Utilization of this program has been lower than anticipated underscoring the importance/challenge of establishing trust and confidence with a purely telehealth provider.

These arrangements are relatively simple for school districts because of their “plug-and-play” nature but may require the school district to cover the full costs of the program, as opposed to generating reimbursement through Medi-Cal or other sources.

Schools can work with local providers and partners to create their own telehealth programs. Because of the COVID pandemic, many more community-based health providers (i.e. community health centers, mental health agencies) have new capacity and expertise in delivering telehealth services. Partnering with these organizations to create telehealth arrangements can be a fruitful strategy for school districts without SBHCs.

These arrangements are relatively simple for school districts because of their “plug-and-play” nature but can cost districts significantly more than a similar community-based service because they are unable to recoup many costs through Medi-Cal, CHIP, or other insurance reimbursement. They also lack natural connections to the local health care safety net and do not typically provide well care or sexual and reproductive health services.

This is a good option for school districts with a low concentration of students who are eligible for free or reduced price meals and for primary school grades. The dedicated help for start-up is positive but may leave school districts with a large price tag.

Schools can work with local providers and partners to create their own telehealth program but this can be complicated and time-consuming. It is best achieved through close partnerships with local health care providers that know the requirements, limitations, legal, and financial terrain. If a school does not have an SBHC and is interested in starting a telehealth program, we recommend they reach out to their local community health center.

CSHA is available to help schools identify and connect them to potential community-based partners. CSHA encourages all schools – especially schools with more than 500 students and a high concentration of those eligible for free and reduced price meals to consider starting an SBHC on their campus.

SBHCs take advantage of in-person relationships to establish trust in a way that not only addresses the health care needs but helps connect students more firmly to school. SBHCs can also help schools create a positive caring school climate.

The schools most likely to find value and have the capacity to house brick-and-mortar SBHCs are large schools with a high proportion of students who are eligible for free and reduced price meals (i.e., Title I schools), since SBHCs are able to generate reimbursement from services delivered to students enrolled in the Medi-Cal program.

Contact us for advice on starting an SBHC.

The California School-Based Health Alliance (CSHA) endorses telehealth services that are age-appropriate, affordable, culturally relevant, cost-effective, and follow sound clinical guidelines.

We recommend that telehealth services be provided by clinicians that are knowledgeable about community resources and local health needs/assets, with the ability to facilitate ongoing care and referrals.

Telehealth providers should connect students to health homes if they have them, share their health records with primary care providers of record, or screen and refer students to other local providers. They should also engage families when appropriate.

- Are your providers local to our community?

- Do they facilitate ongoing care and referrals?

- Do they connect students back to their health home?

- Do you provide behavioral health?

- Do you provide sexual and reproductive health to adolescents?

Local partners can also be leveraged to support telehealth programs.

Anthem Blue Cross, a managed care plan serving approximately 1.3 million members across 29 counties in California and framed as a “digital-first” company, is committed to expanding access to care and improving the health status of children and families.

Together with other managed care organizations, Anthem formed a multi-payer collaborative approach to offer safety net clinics in the Central Valley no-cost access to e-consults to expand access to specialty care.

These plans make e-consults accessible to federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), rural health centers, and Indian Health Centers at no cost. This includes the UCSF Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Portal through which SBHC and other providers can request psychiatry consultations and which includes free one-time virtual visits for SBHCs operated by FQHCs.

To expand the use and availability of telehealth with SBHCs, Anthem is also offering to safety net clinics and SBHCs a no-cost Virtual Case Kiosk Program, which includes a digital kiosk that comes on a rolling cart or stand with multiple video conference applications pre-configured on the iPad.

The digital kiosk can be ideal for SBHCs without a telehealth solution or can be used to expand telehealth services to other local schools.

The Virtual Care Kiosk program works with multiple video conference apps and includes on-demand interpreter services with over 200 languages, very minimal lag time, no cost for Anthem patients, and discounted costs for others.

Additional Resources

The national School-Based Health Alliance has additional telehealth resources specifically for SBHCs.

See the National Center for School Mental Health’s Telemental Health 101 webinar on YouTube.

The National Coalition of STD Directors has a telemedicine toolkit designed to help users consider how telehealth can be used to reach the sexual health needs of adolescents.

The California Primary Care Association has a quick 7-minute video on YouTube: Quality Control in Video Conferencing.

Northwest Regional Telehealth Resource Center’s Quick Start Guide to Telehealth includes information about technology, sample workflow, and legal considerations.

California Association of School Psychologists has a Technology Checklist for School Telehealth Services.